Lunar Frontlines: Project Horizon and the Cold War Dream of a Moon Base

“Lunar Frontlines”

The Cold War Dream of a Moon Base

“The U.S. national policy on space includes the objective of developing and exploiting this Nation's space capability as necessary to achieve national political, scientific, and security objectives.”

—Project Horizon Report, 1959

The year was 1959.

The Cold War was not only heating up—it was climbing upward.

Barely two years earlier, the Soviet Union had shattered American complacency with the launch of Sputnik, the world’s first artificial satellite. For the first time, a hostile ideological power had placed a machine in orbit above American skies—one that could be the precursor to intercontinental nuclear delivery systems launched not from silos, but from the heavens. The American response, at least publicly, was the formation of NASA, a civilian space agency designed to demonstrate the scientific leadership of the free world.

But far from the glare of cameras and press conferences, a more aggressive vision was taking shape.

Within the corridors of the Army Ballistic Missile Agency (ABMA)—led by the controversial former SS officer turned U.S. space architect Wernher von Braun—a classified proposal was being drawn up. Its codename: Project Horizon.

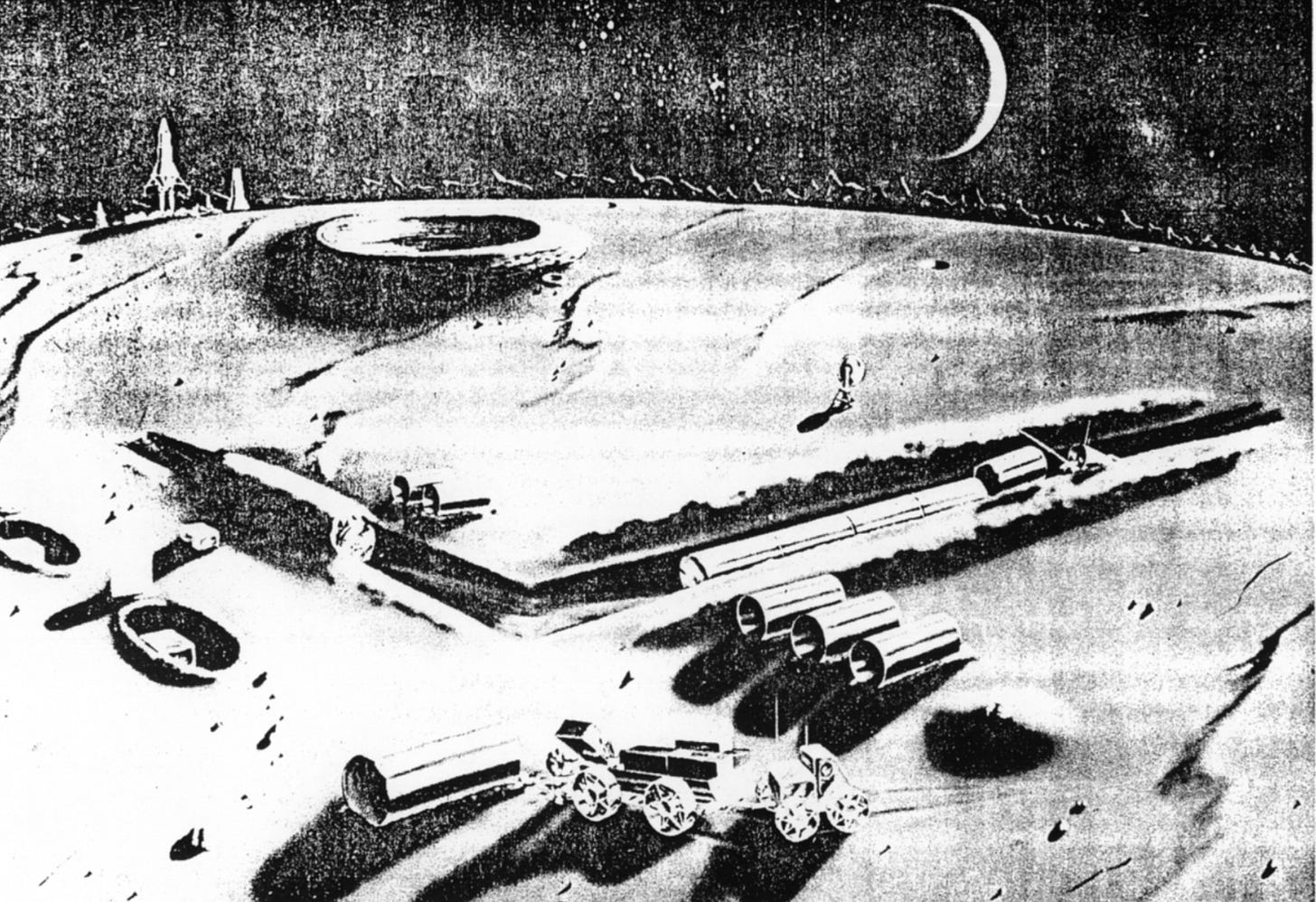

Its objective was both breathtaking and chilling: the establishment of a permanent, manned U.S. military outpost on the Moon by 1966, capable of defending American interests in space, supporting reconnaissance and communications, and—crucially—delivering nuclear weapons from beyond Earth’s atmosphere.

This was no science fiction.

It was a 190-page, multi-volume technical feasibility study commissioned directly by the U.S. Army.

And if it had gone forward, it might have resulted in the Moon becoming a strategic weapons platform, an extraterrestrial extension of mutually assured destruction.

A Strategic “Outpost” in Space

The authors of the Project Horizon report did not mince words about its purpose. “The establishment of a lunar outpost,” the report stated, was necessary to “[demonstrate] the United States scientific leadership in outer space,” and to “extend and improve space reconnaissance and surveillance capabilities and control of space.” It would also serve, they wrote, as a “communications relay station” and as a base for “supporting scientific explorations and investigations.”

But the deeper rationale lay in the subtext—and in the fears of the Pentagon.

In the aftermath of Sputnik, space had ceased to be a neutral domain. The psychological impact of the Soviet satellite’s beep-beep over American cities had triggered a strategic shift. The Eisenhower administration, already cautious about a runaway military-industrial complex, had initially sought to keep space civilian. But the Department of Defense saw something else: a new high ground.

Civilian Dreams vs Military Realities

The formation of NASA in 1958 was intended to consolidate civilian space exploration. Yet even in the language of the Eisenhower White House, space was not merely for telescopes and astronauts—it was a domain of “prestige, power, and security.” As noted in the GovInfo briefing, the United States space program was always dual-purpose, even when presented as purely scientific.

Tensions between NASA and the Department of Defense would come to define the decade. The Civilian-Military Liaison Committee and the National Aeronautics and Space Council were created in part to referee this uneasy marriage. On paper, NASA would lead the peaceful exploration of space. In practice, the Department of Defense retained vast influence—particularly through programs like Project Mercury, Dynasoar, Gemini, and the military’s own Manned Orbiting Laboratory (MOL).

But it was Project Horizon that came closest to claiming the Moon as a theatre of Cold War operations.

A Vision Buried

Why was the plan never executed?

The official reasons are mundane: budget concerns, bureaucratic overlap, and the eventual preference for NASA’s civilian Apollo Program, which better aligned with the public-facing narrative of peaceful lunar exploration.

But the unofficial reasons? Those are more telling.

The Moon, if militarised, would have become a flashpoint—an orbital Berlin, a place where even a whisper of aggression could cascade into thermonuclear war. As international concerns about the weaponisation of space mounted, and as the Outer Space Treaty began to take shape, the wisdom of turning the Moon into a forward base came into question. A nuclear-tipped lunar bunker might protect America’s dominance—but at the cost of triggering Armageddon from above.

And so Project Horizon was shelved.

Not because it was impossible—but because it was too possible.

Still Haunting the Present

Today, when the Space Force speaks of “cislunar operations,” when China and Russia discuss the strategic value of the Moon’s poles, and when DARPA funds lunar infrastructure studies, we are not entering new territory—we are revisiting old ones.

And in the vaults of declassified archives, Project Horizon stands not as a relic, but as a blueprint—a glimpse of the path not taken… yet.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Hangar 51 Files to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.